NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver happens when fat-related liver damage reaches a late stage with deep scarring. The scars block normal blood flow and weaken liver work. This stage develops after years of silent injury tied to metabolism and inflammation. You may feel fine early, yet internal changes progress. Care can slow harm, but scars rarely reverse once formed.

Table of Contents

ToggleFeatured Snippet Block

- NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver is a severe stage of fatty liver disease marked by permanent scarring.

- It follows long periods of fat buildup and inflammation inside liver cells.

- Blood flow and detox function decline as structure changes.

- Early detection slows worsening.

- Damage usually stays permanent, yet proper care lowers complications and supports stability.

What Is NAFLD Cirrhosis Of The Liver?

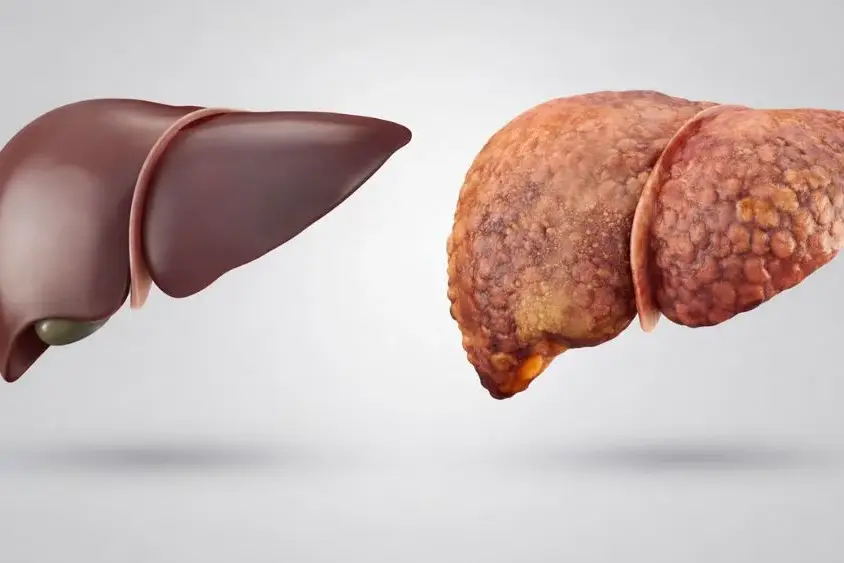

NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver describes extensive scarring after chronic fat-driven injury. Healthy liver cells die. Fibrous tissue replaces them. This tissue cannot perform normal work. Blood vessels twist and narrow. Pressure builds in surrounding veins. This process harms detoxification and nutrient handling.

Biologically, cirrhosis means the liver’s architecture changes. Instead of smooth tissue, nodules form. Nodules are small lumps of regenerating cells trapped between scars. Flow resistance rises. Oxygen delivery drops. Toxin removal weakens. These structural changes define non-alcoholic fatty liver cirrhosis rather than temporary inflammation.

Progression starts quietly. Excess fat enters liver cells. Immune activity rises to respond. This stage may develop into MASH (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis). Hepatitis refers to inflammation. Persistent inflammation injures cells repeatedly. Fibrosis develops. Fibrosis means scarring. Long-standing fibrosis transforms into NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver .

Difference in brief terms:

| Stage | What Happens |

| Fatty liver | Fat present without injury |

| MASH | Fat plus inflammation and cell damage |

| Cirrhosis | Permanent scarring and structural distortion |

Not everyone with a fatty liver ends up with non-alcoholic fatty liver cirrhosis . Only about 20% of people with MASH progress to this advanced stage. But those who do face serious health consequences.

NAFLD Cirrhosis Causes

The term NAFLD cirrhosis causes refers to factors that sustain injury rather than one-time triggers. Progression requires long exposure to metabolic strain and inflammatory signaling.

Long-Term Metabolic Causes

Chronic insulin resistance drives the entire process. When you eat carbohydrates, your pancreas releases insulin to help cells absorb sugar from your bloodstream. But when cells stop responding properly to insulin (a condition called insulin resistance), sugar stays elevated in your blood.

Your liver responds by converting that excess sugar into fat. Over months and years, fat accumulates faster than your liver can package it up and send it out. The fat droplets crowd out normal liver cells.

Type 2 diabetes accelerates everything. High blood sugar combined with high insulin levels creates the perfect environment for liver damage. People with diabetes develop NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver at rates two to three times higher than people without diabetes.

Disease Progression Factors

Untreated MASH is the critical bridge between simple fatty liver and cirrhosis. When inflammation persists without treatment, liver cells die in large numbers. Your body tries to repair the damage by laying down scar tissue; it accumulates layer upon layer.

Damaged liver cells release danger signals that attract immune cells. These immune cells arrive trying to help, but they release more inflammatory chemicals that cause additional damage. The process spirals. Each wave of inflammation kills more liver cells and deposits more scar tissue.

Genetic susceptibility explains why some people progress to NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver while others with similar lifestyles don’t. A gene variant called PNPLA3 (patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3) strongly influences how your liver handles fat and responds to injury. People carrying certain versions of this gene accumulate fat more easily and scar more readily.

Another gene called TM6SF2 affects how your liver packages and exports fat. Variations in these genes don’t guarantee you’ll develop cirrhosis, but they significantly increase your risk.

NAFLD Cirrhosis Symptoms

Monitoring NAFLD cirrhosis symptoms requires stage awareness. Early stages compensate. Late stages reveal organ strain. Recognition supports timely evaluation.

Early Compensated Symptoms

Most people with early cirrhosis feel completely normal. Your liver has remarkable reserve capacity, capable of losing more than 60% of its function before symptoms appear.

Mild fatigue may occur. Energy production alters due to metabolic imbalance. This sign lacks specificity. Many overlook it.

Digestive discomfort may appear. Fullness develops sooner. Occasional bloating occurs. These signals remain subtle.

Blood tests might show slightly elevated liver enzymes (proteins that leak from damaged liver cells), but even these can be normal. Up to 30% of people with compensated cirrhosis have normal enzyme levels because the liver isn’t actively inflamed anymore, just scarred. This makes routine screening important for people with risk factors.

Advanced Decompensated Symptoms

Advanced NAFLD cirrhosis symptoms reflect declining function.

- Ascites refers to fluid accumulation in the abdomen. Portal pressure shifts fluid outward. Clothing feels tighter.

- Jaundice causes yellow discoloration. Bilirubin builds up. Bilirubin is waste pigment normally processed by the liver.

- Confusion indicates hepatic encephalopathy. Toxin buildup affects brain activity. Memory and focus drop.

- Bleeding tendency appears. Clotting protein production declines. Minor injuries bleed longer.

When these signs appear, evaluation for NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver becomes urgent. Early intervention helps manage complications and maintain stability.

How NAFLD Cirrhosis Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis of NAFLD at the cirrhosis stage requires multiple tests such as, your medical history, physical examination, blood work, and imaging studies.

Blood tests reveal important clues but have significant limitations.

- Liver enzymes (ALT and AST) measure proteins that leak from damaged cells. However, these enzymes can be completely normal even with advanced NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver because a scarred liver that’s no longer inflamed won’t release high levels of enzymes.

- Albumin (a protein your liver makes) drops when liver function declines.

- Bilirubin rises when the liver can’t process it.

- Platelet counts often fall because an enlarged spleen traps them.

- Prothrombin time (a clotting test) becomes prolonged when the liver can’t produce clotting factors.

Imaging provides visual confirmation of scarring.

- FibroScan uses ultrasound waves to measure liver stiffness. Healthy liver tissue is soft and elastic. Scarred tissue is hard and rigid. The machine assigns a stiffness score measured in kilopascals. Scores above 12-14 kPa suggest cirrhosis.

- Standard ultrasound shows a shrunken liver with a bumpy, nodular surface instead of smooth edges. The liver’s texture appears coarse. Ultrasound also detects ascites, an enlarged spleen, and widened blood vessels that indicate portal hypertension.

- CT scans and MRI provide detailed cross-sectional images. MRI with elastography combines imaging with stiffness measurement for comprehensive assessment.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard, but isn’t always necessary. A radiologist inserts a thin needle through your skin between your ribs and removes a tiny tissue sample to study the scarring pattern and grade its severity. Biopsy carries small risks including bleeding and infection, so doctors reserve it for cases where imaging and blood tests give conflicting results or when knowing the exact stage will change treatment decisions.

Treatment Of NAFLD Cirrhosis

Treatment of NAFLD at the cirrhosis stage focuses on halting progression and managing complications since the scarring itself cannot be removed.

Slowing disease progression starts with weight loss. Losing 7-10% of your body weight reduces liver inflammation and can prevent additional scarring from forming. But the weight loss must be gradual, about 1-2 pounds per week. Rapid weight loss actually worsens liver inflammation because fat breaks down too quickly and overwhelms the liver.

- Diuretics like spironolactone and furosemide help your kidneys eliminate excess fluid to reduce ascites. You’ll need to restrict salt intake to less than 2 grams daily because salt makes your body retain water.

- Lactulose, a synthetic sugar, prevents hepatic encephalopathy by reducing ammonia absorption from your intestines. It works by changing the pH in your colon and promoting beneficial bacteria. You take it two to three times daily, adjusting the dose until you have two to three soft bowel movements per day.

- Beta-blockers like propranolol or carvedilol lower portal hypertension and reduce the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices.

Controlling diabetes becomes critical. Medications like GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide, liraglutide) and SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) not only improve blood sugar control but also reduce liver fat and inflammation.

Cirrhosis increases your risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) by 20-30 times. You need ultrasound imaging and AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) blood tests every six months. AFP is a protein that rises in many liver cancers. Early detection means tumors can be treated with ablation, resection, or transplant before they spread.

Liver transplant represents the only cure for end-stage NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver . When your liver fails completely and complications become life-threatening, transplant becomes the lifesaving option. NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver now ranks as one of the top indications for liver transplant in the United States and Europe.

The five-year survival rate after transplant exceeds 75%. However, if you don’t address the underlying metabolic problems, fat can accumulate in the new liver too.

Can NAFLD Cirrhosis Be Reversed?

Cirrhosis scarring is permanent in most cases. Scar tissue that has already formed doesn’t transform back into healthy liver cells.

However, liver function can stabilize and even improve if you eliminate the underlying causes. When you lose weight, control diabetes, and stop ongoing inflammation, the remaining healthy liver tissue works more efficiently.

Some people with compensated NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver maintain stable liver function for 10-15 years or longer. Their cirrhosis doesn’t progress, and they avoid serious complications.

The liver’s regenerative capacity is remarkable. Even with 30-40% healthy tissue remaining, it can perform most essential functions if that tissue isn’t under constant attack.

NAFLD Cirrhosis And Life Expectancy

Prognosis varies dramatically based on multiple factors. Some people with compensated non-alcoholic fatty liver cirrhosis live 15-20 years without major problems. Others with decompensated cirrhosis face median survival of 2-5 years without transplant.

Compensated cirrhosis has a median survival exceeding 12 years. Your liver still performs most functions despite the scarring. But once decompensation occurs (marked by ascites, jaundice, bleeding, or encephalopathy), median survival drops to about 2 years. Each complication that develops worsens the outlook further.

Complications drive mortality risk.

- Variceal bleeding (ruptured veins in your esophagus) carries 20-30% mortality during the first episode.

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (infection of ascitic fluid) kills 20-40% of patients during the first infection.

- Hepatorenal syndrome (kidney failure triggered by cirrhosis) has extremely poor outcomes without transplant.

- Hepatic encephalopathy progression leads to coma and death.

Access to specialist care makes measurable differences in outcomes. Seeing a hepatologist regularly improves survival rates by 20-30% compared to general medicine care alone.

FAQ

Can NAFLD cause cirrhosis of the liver?

Yes. NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver develops when fatty liver inflammation persists for years ,untreated. About 20% of people with MASH progress to cirrhosis over 10-20 years. The risk increases sharply with diabetes and obesity.

Is NAFLD cirrhosis reversible?

No, the scarring is permanent. However, liver function can stabilize if you control diabetes, lose weight, and stop ongoing inflammation. Early intervention before cirrhosis offers the only chance for true reversal of liver damage.

Does NAFLD cirrhosis require alcohol use?

No. Non-alcoholic fatty liver cirrhosis occurs without any alcohol consumption. It’s driven by insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity, not drinking. Many patients with this condition have never consumed alcohol regularly.

Can NAFLD cirrhosis exist without symptoms?

Yes. Compensated NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver often causes zero symptoms for years. Your liver can lose over 60% of its function before you notice problems. This silent progression makes screening critical for high-risk individuals.

Is NAFLD cirrhosis life-threatening?

Yes, especially decompensated cirrhosis. It leads to liver failure, internal bleeding, kidney failure, and infections that can be fatal without transplant. Even compensated cirrhosis increases death risk from liver cancer.

Does NAFLD cirrhosis increase cancer risk?

Yes, dramatically. NAFLD cirrhosis of the liver raises hepatocellular carcinoma risk 20-30 fold. You need ultrasound and AFP blood tests every six months for early detection when treatment remains possible.

Is transplant the only cure?

Yes, for end-stage disease. Liver transplant replaces your scarred liver with a healthy donor organ. Five-year survival after transplant exceeds 75%. It’s not needed for early compensated cirrhosis that remains stable.

Can progression be slowed?

Yes, absolutely. Weight loss of 7-10%, diabetes control with newer medications, and eliminating metabolic stressors prevent additional scarring. Medical management of portal hypertension reduces complication risks and extends survival significantly.

About The Author

Medically reviewed by Dr. Nivedita Pandey, MD, DM (Gastroenterology)

Senior Gastroenterologist & Hepatologist

Dr. Nivedita Pandey is a U.S.-trained gastroenterologist and hepatologist with extensive experience in diagnosing and treating liver diseases and gastrointestinal disorders. She specializes in liver enzyme abnormalities, fatty liver disease, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and digestive health.

All content is reviewed for medical accuracy and aligned with current clinical guidelines.

About Author | Instagram | Linkedin