What the liver does comes down to constant chemical control over your internal environment. The liver receives nutrient-rich blood from digestion, converts carbohydrates into stored glycogen, processes fats and proteins, produces bile for fat absorption, and neutralizes drugs, alcohol, and metabolic waste before circulation spreads them further.

Table of Contents

ToggleIt also synthesizes clotting proteins, regulates hormone breakdown, stores vitamins and minerals, and filters microbes entering from the gut.

Featured Snippet

- The liver manages nutrients, toxins, metabolism, and storage

- It produces bile for fat digestion

- It controls blood sugar and protein synthesis

- It stores vitamins and minerals

- It protects against microbes entering through the gut

What Does The Liver Do In The Body?

What the liver does comes down to survival maintenance. You rely on this organ to process nearly everything that enters your bloodstream from food, medicine, or environmental exposure.

Located beneath the right rib cage, it receives nutrient-rich blood from the intestine and chemically alters those nutrients before distribution. This central handling role explains why the liver’s function in the body extends beyond digestion and touches metabolism, immunity, and storage regulation.

T he liver function is grouped into several integrated systems rather than separate jobs.

- It assists digestion by producing bile.

- It regulates metabolism by managing carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

- It neutralizes potentially harmful compounds through enzymatic modification.

- It stores reserves such as vitamins and minerals.

- It contributes to immune filtering. Because each process operates continuously, the liver’s function in the body affects health every minute.

The organ also demonstrates structural specialization. Dual blood supply allows it to handle oxygenated blood and nutrient-heavy portal blood simultaneously. Hepatocytes, the main working cells, conduct chemical transformations, while immune cells intercept microbes entering from the gut.

Liver Detoxification Function

The liver detoxification function describes the biochemical conversion of compounds that could damage tissues if allowed to circulate unchanged. Detoxification means altering molecules using enzymes rather than physically flushing substances out. You encounter this function when medications enter your system, alcohol gets absorbed, or hormones finish their signaling cycles.

How The Liver Removes Toxins

- Blood from the digestive tract flows directly to the liver through the portal vein.

- This routing exposes absorbed compounds to metabolic enzymes before wider distribution.

- These enzymes transform molecules into forms that kidneys or bile pathways can eliminate.

Environmental toxin handling adds complexity. Heavy metals and industrial pollutants may undergo partial processing and storage rather than immediate elimination. The liver detoxification function remains the primary defense against internal chemical overload.

What Detoxification Actually Means

Public marketing often equates detoxification with dietary cleanses. The liver detoxification function depends on enzyme systems such as oxidases and transferases. These protein catalysts transform compounds automatically. External drinks cannot replace these cellular pathways.

Detoxification means conversion, not removal by beverages. The liver changes chemical structure so excretion organs can finish elimination.

What Does The Liver Do For Digestion?

What the liver does for digestion centers on bile production, a fluid essential for handling dietary fats. Bile contains bile acids derived from cholesterol. These acids break fat into small droplets, increasing accessibility to digestive enzymes.

Without bile, fat absorption declines significantly. You may experience poor uptake of fat-soluble vitamins, including A, D, E, and K. These vitamins regulate vision, bone health, antioxidant activity, and blood clotting. Therefore, understanding what the liver does for digestion extends beyond fats and reaches micronutrient availability.

Another aspect of how the liver helps digestion involves waste transport. Bile carries certain metabolic byproducts toward elimination. This function prevents buildup of compounds such as bilirubin, a pigment produced during red blood cell turnover. When bile flow disrupts, accumulation causes yellowing of skin and eyes.

The digestive support role remains indirect. The liver does not contact food particles physically. Instead, it prepares chemical tools that allow intestinal enzymes to complete nutrient breakdown.

Liver Function In Metabolism

The liver’s function in metabolism involves controlling energy availability and structural molecule production. This regulatory influence becomes clearer when nutrient categories are examined separately.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

- After eating, excess glucose enters hepatocytes and is converted to glycogen, a stored carbohydrate form.

- During fasting, glycogen breaks down into glucose and returns to circulation.

- This buffering stabilizes blood sugar levels, especially during sleep or exercise.

- Through this process, the liver ensures the brain receives a constant energy supply despite changing intake patterns.

Additional pathways create glucose from non-carbohydrate sources when reserves drop. This capacity becomes vital during prolonged fasting or illness.

Fat Metabolism

Fat processing includes cholesterol synthesis, lipoprotein formation, and redistribution of fatty molecules throughout the body. Lipoproteins transport fats through watery blood environments. Disruption of these processes alters cardiovascular risk markers.

Fatty acid oxidation also produces energy during low-carbohydrate states. However, excessive accumulation leads to cellular stress.

Protein Metabolism

Protein handling completes metabolic oversight. The liver synthesizes albumin and clotting factors. Albumin maintains fluid distribution between vessels and tissues, while clotting factors prevent uncontrolled bleeding.

Nitrogen waste processing further reflects the liver’s function in metabolism . Ammonia generated during protein breakdown converts into urea, which the kidneys remove. Failure of this process leads to neurological impairment due to toxin accumulation.

Liver Storage And Regulatory Functions

You rely on storage activity more than you notice, because nutrient availability does not match daily intake patterns. Liver’s storage functions stabilize the supply of vitamins, minerals, and circulating blood volume while regulating release based on physiological signals.

Vitamin storage includes fat-soluble compounds that accumulate within hepatic tissue for controlled distribution.

- Vitamin A supports vision and skin health.

- Vitamin D assists bone mineral balance.

- Vitamin B12 remains stored for years and supports nerve function and red blood cell production.

This reserve capacity reflects the liver function in the body , preventing deficiency during limited intake periods.

Mineral handling follows similar regulations.

- Iron binds to ferritin proteins and is released when bone marrow requires it for hemoglobin synthesis.

- Copper participates in enzyme reactions and remains tightly controlled because excess copper damages tissues.

Blood reservoir capability provides another regulatory role. The liver can temporarily store a portion of circulating blood and release it during injury or fluid imbalance. This buffering helps maintain circulation pressure and oxygen delivery, reinforcing systemic aspects of the liver function in the body .

Immune And Protective Functions Of The Liver

Protection against microbes entering from the intestine occurs continuously. Blood arriving from digestive organs often carries bacterial fragments or toxins, and hepatic immune cells intercept them before systemic spread.

Kupffer cells, a type of macrophage (immune scavenger cell), capture pathogens and debris within liver sinusoids (small blood channels). This clearance reduces inflammatory burden and prevents bloodstream infection.

Antigen presentation also occurs here. Antigens are molecular markers that trigger immune recognition. The liver participates in moderating immune response intensity, preventing overreaction to harmless dietary proteins while still responding to threats.

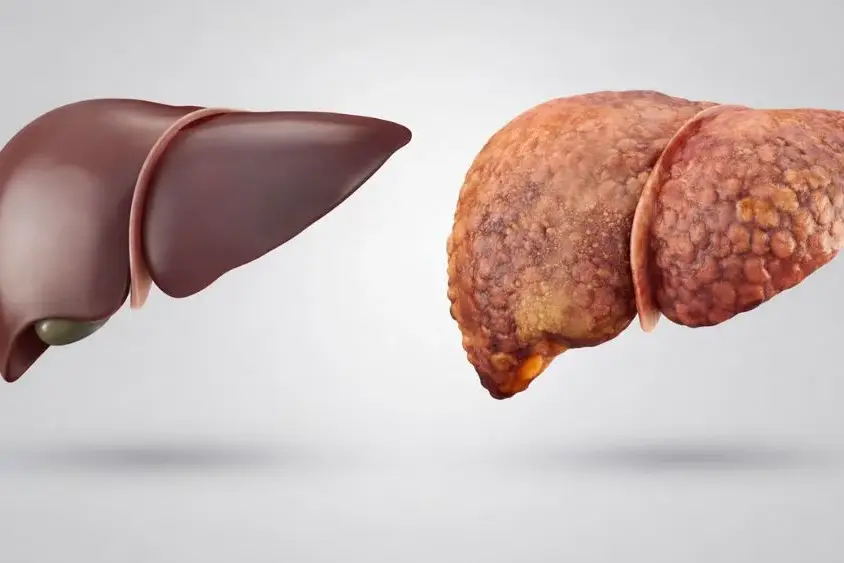

What Diseases Can Develop In The Liver?

- Fatty liver disease results from excessive lipid deposition inside hepatocytes. It is often associated with insulin resistance and sedentary lifestyle patterns.

- Hepatitis refers to inflammation commonly triggered by viral infection or toxin exposure.

- Cirrhosis develops when repeated injury replaces healthy tissue with scar structures. Cancer arises when cellular regulation fails.

Understanding what diseases can develop in the liver requires noting those early stages. Screening through laboratory markers and imaging often detects abnormalities before discomfort appears.

Risk distribution varies globally due to diet, alcohol use, viral prevalence, and environmental exposure. Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors significantly influence incidence patterns.

What Happens When The Liver Stops Working Properly?

Functional decline disrupts internal balance quickly because numerous systems depend on hepatic processing.

Early impairment often affects metabolic control.

- Blood glucose regulation becomes inconsistent, and toxin clearance efficiency drops.

- Reduced protein synthesis lowers albumin levels, leading to fluid accumulation in tissues.

- Neurological effects may appear when ammonia levels rise due to impaired conversion into urea. This condition affects cognition and coordination.

- Clotting abnormalities develop because factor production declines.

Symptoms typically emerge late because nerve density within liver tissue remains low. Disease progression may remain unnoticed until measurable dysfunction occurs.

Common Myths About Liver Function

- The claim that the liver only processes alcohol ignores its broader metabolic and immune contributions.

- Belief that damage produces early pain conflicts with anatomical reality of limited sensory signaling.

- Marketing narratives suggesting detox diets enhance enzymatic capacity lack consistent supporting evidence beyond correcting nutrient deficiencies.

FAQs – What Does The Liver Do?

Is the liver essential for life?

Yes. The liver is involved in glucose regulation, toxin metabolism, and clotting protein production. Without these processes, metabolic collapse occurs within days, and survival requires organ transplantation or artificial support technologies.

Does the liver help with digestion?

Yes. The liver’s role in digestion includes producing bile acids that emulsify fats, enabling vitamin A, D, E, and K absorption and preventing lipid malabsorption that can cause nutrient deficiency and gastrointestinal disturbance.

Does the liver detox the body?

Yes. The liver involves enzymatic modification of drugs, hormones, and pollutants so kidneys or bile pathways remove them. This biochemical conversion forms the basis of the liver detoxification function .

Does the liver control metabolism?

Yes. The liver includes storing glycogen, synthesizing cholesterol carriers, producing albumin, and converting ammonia to urea. These processes demonstrate central liver function in the body, affecting energy, circulation, and neurological safety.

Can the liver stop working without symptoms?

Yes. Liver disease continues silently during early injury because nerve density is low. Conditions like fatty infiltration or viral inflammation may progress for years before laboratory abnormalities or imaging changes appear.

Does the liver store nutrients?

Yes. The liver retains vitamins A, D, and B12 plus iron reserves. This storage stabilizes supply during poor intake and reflects essential regulatory liver function in the body .

Is liver damage reversible?

Sometimes. The liver may recover when injury stops early, such as lifestyle-related fatty accumulation. Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis often remains permanent due to structural tissue replacement.

Does alcohol affect all liver functions?

Yes. The liver becomes impaired because alcohol metabolism alters fat handling, protein synthesis, immune response, and detox pathways, extending beyond simple toxin processing disruption.

About The Author

Medically reviewed by Dr. Nivedita Pandey, MD, DM (Gastroenterology)

Senior Gastroenterologist & Hepatologist

Dr. Nivedita Pandey is a U.S.-trained gastroenterologist and hepatologist with extensive experience in diagnosing and treating liver diseases and gastrointestinal disorders. She specializes in liver enzyme abnormalities, fatty liver disease, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and digestive health.

All content is reviewed for medical accuracy and aligned with current clinical guidelines.

About Author | Instagram | Linkedin